May You Be Blessed by the God of Your Heart

|

The Importance of Biblical Translations to Protestantism

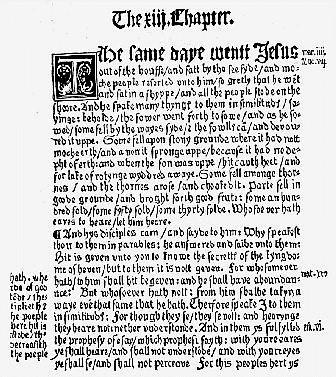

Wycliffe's TranslationThe Bible was originally written in differing languages then common to the Middle East. The Jewish Bible, or the Old Testament, was originally written in Hebrew, with some passages in Aramaic. The New Testament was originally written in Koine Greek, the common language used in the eastern Mediterranean basin in the time of Jesus. As the Gospel, or "good news" spread to other peoples and tongues, translations of the holy scriptures became necessary. The first translations of the scriptures were poetic renderings of biblical stories and passages into Anglo-Saxon by an especially gifted monk, Caedmon, in the seventh century CE. Translations of the Psalms and other short passages were made into Old English in the ninth and tenth century CE. Alfred the Great created the Lindesfarne gospels. These translations were made to teach the common people somewhat of the Gospel in their native tongue. The only version of scripture then generally used was St. Jerome's Latin Vulgate, in the language of the Church and of the learned. There existed at this time a group of Christians, generally persecuted by the Church as heretics, known in Italy as the Waldensians. Most modern writers attribute their existence to one Peter Waldo in 1175, but evidence suggests that their communion may have existed much earlier. The Waldensians used vernacular translations of the scriptures in both the French and Italian languages in their street ministries as early as 1300, and may have had a much older "Italick" translation based on the Textus Receptus. The scholar Theodore Beza dated the founding of the Waldensian Church to 120 CE (Fuller, pp. 207-209). John Wycliffe (ca. 1320-1384) was an English reformer who believed in the primacy of the scriptures, and argued for a version of the Bible in the vernacular tongue. On this and on other issues he was opposed by the Church. Drawing on the Latin Vulgate, Wycliffe started translating the New Testament in 1380. After his death, the translation was completed by his friends (Kirkbride, p. 181).

Gutenberg's Printing PressPerhaps the single most important invention in aiding the advent of the Renaissance and the Protestant Reformation was the printing press. Johann Gutenberg is credited with the invention of the moveable type printing press. His first and only publication of any certainty is the Gutenberg Bible, published in 1452. Previous to Gutenberg, books had to be meticulously handcopied. Availability was extremely limited and books were extremely costly. The invention of the printing press allowed for virtually an unlimited number of copies. Although books were still out of the reach of the common people, they became available to more people. Eventually, a number of scholarly religious books became available such as Desiderius Erasmus' Greek New Testament (in 1516), the Hebrew text of the Old Testament, and the Jewish Talmud. With such references available, more Christian scholars became interested in providing biblical translations in the common tongue.

William TyndaleWilliam Tyndale (or Tindale) was born ca. 1490 in Gloucester, England of noble heritage. He received the finest education available and studied Greek with Erasmus in 1510-1514. It was the desire of Tyndale to allow the common man to read the scriptures for themselves. To a priest, the young Tyndale once said, "Ere many years, God willing, I shall make the ploughman to know more of the scriptures than thou" (Sawyer, p. 2). Tyndale was persecuted by the Church for his belief and fled to the continent to continue his work. His New Testament was published in 1525 and the Pentateuch in 1530. His work was unique in that it was the first English translation to depend solely upon the original Greek, rather than the Latin translation. It became the basis for later English translations of the Bible (Kirkbride, p. 181). As copies made their way into England, they were seized and burned. Those who read this New Testament were imprisoned, and some were killed. Cuthbert Tonstall, Bishop of London, issued a decree prohibiting the English New Testament. He commissioned a merchant to purchase the majority of the books and burned them at St. Paul's cross in 1528. Eventually, Tyndale and his associates were caught and sentenced to death. Tyndale was strangled and then burned at the stake in 1536. His dying words were, "Lord, open the King of England's eyes". So thorough were the efforts of the authorities, that only two copies of Tyndale's New Testament are in existence today (Sawyer, pp. 1-13).

The Geneva BibleOther translations were soon to follow. Miles Coverdale, a friend of Tyndale, using Tyndale's version and the Latin as helps, he prepared a Bible dedicated to Henry VIII in 1535. It is thought that a friend of Tyndale's, John Rogers, had possession of some of Tyndale's Old Testament manuscripts. When Matthews' Bible appeared in 1537, it was believed to have actually been produced by John Rogers. The Great Bible, drawing from Matthews, Coverdale, and Tyndale, appeared in 1539. It was ordered to be set up in every parish church. The Great Bible was a huge book and was typically chained to the reading desks in churches where people were able to gather around it to hear the word of God read. The Geneva Bible was published in 1560. The translation was done in Geneva, Switzerland by scholars fled from Queen Mary's persecution. The Geneva Bible was a revision of the Great Bible with copious notes by the Reformers. As each edition was published, additional notes by the Reformers were included, adding to the usefulness of the Bible and fueling the flames of the Reformation. It was the Geneva Bible that the Puritans took to America; not the King James Version which they thought was too modern! Other versions followed. The Archbishop of Canterbury directed the preparation of the Bishop's Bible in 1568. Jesuits, seeking to offset the supposed heresies of the other translations, published a New Testament in Rheims, France in 1582. After the Old Testament was finished in Douay, France, the complete Douay-Rheims Bible followed in 1609. Until recently, the Douay-Rheims Bible was the standard English Bible of the Roman Catholic Church. (Kirkbride, p. 181).

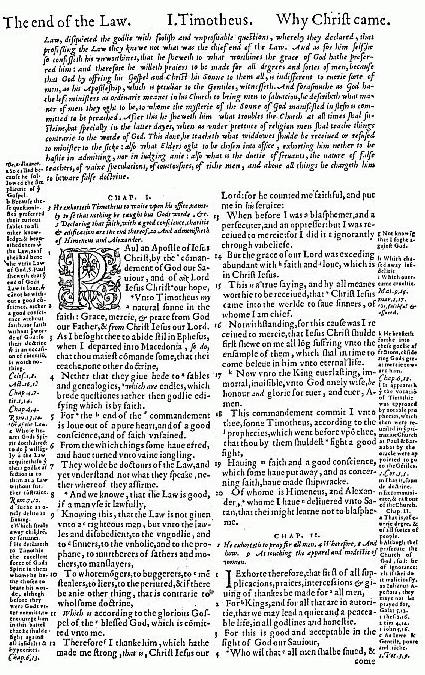

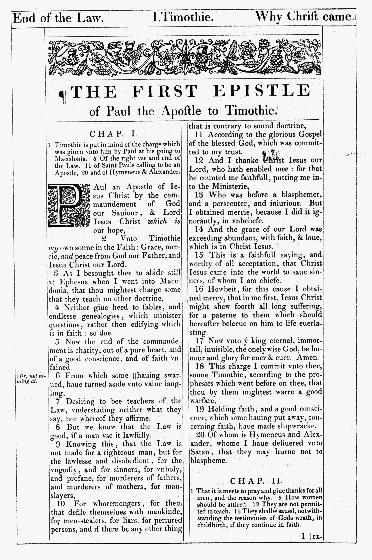

The King James VersionThe words chosen by the translators of the Geneva Bible coupled with the notes of the Reformers favored a more law oriented view of the Christian message. Others, with more of a grace orientation sought the attention of King James I. They believed that a revision of the Bible was necessary to promote a more antinomial theological stance. King James I agreed and authorized the new translation. The new translation was made from the original Greek and Hebrew texts by a panel of forty-seven scholars, using the Bishop's Bible as a guide. The men chosen were some of the most learned of their day, many of whom were also devoted Christians. The new translation, called the Authorised or, later, the King James version was first published in 1611. In their introductory, "The Translators to the Reader", the translators wrote: But now what piety without truth? What truth (what saving truth) without the word of God? What word of God (whereof we may be sure) without the scripture? The scriptures we are commanded to search (Joh. 5:39, Isa. 8:20). They are commended that searched and studied them (Acts 17:11; 8:28,29). They are reproved that were unskilled in them, or slow to believe them (Mat. 22:29, Luk. 24:25). They can make us wise unto salvation (2 Tim. 3:15). If we be ignorant, they will instruct us; if out of the way, they will bring us home; if out of order, they will reform us, if in heaviness, comfort us; if dull, quicken us; if cold, inflame us (Nelson, p. 2; original spelling was corrected to modern). That said, the most widely sold book in the world was launched. Succeeding generations based their faith as well as their lives and their fortunes upon this book. And more importantly for our study, the King James Version provided the vehicle for an ever increasing number of Protestant sects, all based on their understanding of the text. It was not until many years later that an increasingly larger number of Christian believers were given greater access to the original languages of the Bible. Until then, the King James Bible was the ultimate authority for most Protestant Christians.

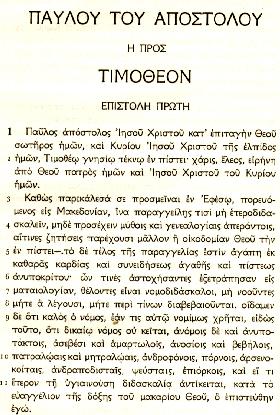

Today's Plethora of Bible TranslationsThrough the years, the King James was gradually revised from the original 1611 edition. New discoveries of differing types of the original Greek texts eventually led some scholars to believe that the Textus Receptus, or the "Received Text" of the Greek New Testament generally accepted by the Church, was somehow flawed by having been copied and recopied through the years. The comparison of the Received Text with the other text types led to the study of Textual Criticism. Textual Criticism eventually became yet another issue which divides fundamentalist Christians from liberal Christians. Westcott and Hort became among the first to seriously study the newly discovered Alexandrian text type. Their studies eventually led to the production of a new Greek New Testament, differing from the Textus Receptus. The translation of the Greek New Testament into English became the basis for the Revised Version of 1881. A version of this revision better liked by the American committee on revision produced the American Standard Version. As the language of the King James and the revised versions became increasingly perceived as archaic, calls went out for Bibles in the modern language. This led to the release of the such currently popular translations as the Good News Bible, the New International Version, and the New American Standard Bible. Nearly all of these newer versions are based on the Alexandrian text type which is why they are often rejected by fundamentalists. Yet, as the list of new translations continues to grow, the Christian message of the "good news" of Christ reaches an ever widening audience.

ReferencesB.B. Kirkbride Bible Company, Inc., The Thompson Comprehensive Bible Helps. Indianapolis, IN: B.B. Kirkbride Bible Company, Inc., 1964. Part of the popular Thompson Chain Reference Bible.Bede, The Venerable (Leo Sherley-Price, translator), A History of the English Church and People. Baltimore, MD: Penguin Books, 1968. Forbush, William Byron, D.D., (Editor), Fox's Book of Martyrs. Grand Rapids, MI: Clarion Classics, 1967.

Fuller, David Otis, D.D., Which Bible?. Grand Rapids, MI:

Grand Rapids International Publications, 1975. A thorough and educated look

at question of textual criticism and the text types used today in translation

from the fundamentalist viewpoint.

Metzger, Bruce M., A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament.

Stuttgart, Germany: United Bible Societies, 1975. The book provides the

justifications of the scholars for changes made to the Greek New Testament

based on manuscript evidence. The introduction contains a concise explanation

of textual criticism from the scholars favoring textual criticism. A

knowledge of New Testament Greek would make this book more useful.

Trinitarian Bible Society, E Kaine Diatheke, The New Testament.

London: Trinitarian Bible Society, 1985.

|